|

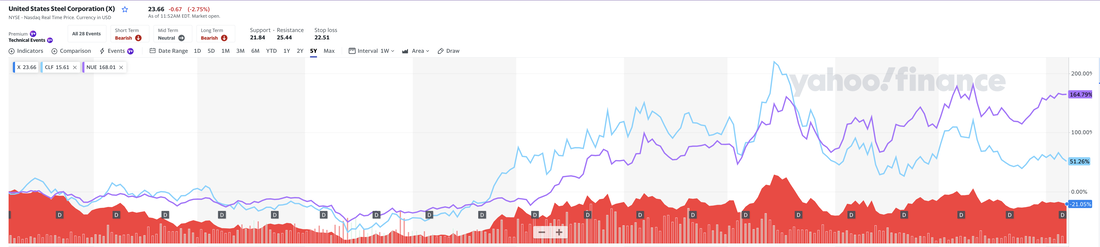

By Jeffrey Cohen President & Founder US Advanced Computing Infrastructure, Inc. So, I was walking through the data and "POW" I was hit in the face by a strange fact. There are many companies with negative book value (or common equity). Taken at 'face value' this means that the companies are bankrupt once they really look at it. Their liabilities exceed their assets. For example, $TUP Tupperware Brands Corporation has negative common equity of $175.4mm, market cap of $252mm, and debt of $688mm. My guess is their assets are worth in the ballpark of $500M. They lose money (negative net income) and lose money off the books (AOCI is negative), so I don't see how they will ever pay back that debt. Taken at a conservative yield of 12% for high yield junk debt, this debt will cost them $82M / year, and no tax shield, so they really do spend that. So, unless the market for sealable plastic containers I buy at Dollar Tree $DLTR sees exponential growth, their fate is sealed, and they will likely have to restructure. So many more examples. If we remove stocks from the 2,663 included in last night's analysis that have negative common equity, then 189 companies drop out. This leaves us 2,474 stocks remaining with positive common equity. Is there a valid ratio for market capitalization vs. common equity? The ratio ranges from less than one (actually around 0.1 or 10% of book value), and up to 6,749 or 674,900% of book value for $CLX or Clorox Co. A windsorized range (~5% off each end) is (0.73, 14.7). The typical US equity trades at somewhere between 73% of book value and 1,470% of book value). It seems to me that logically, we should be valuing companies by taking into account their book value, and their earnings. That does not seem to be the case with Clorox, which has a market capitalization of $20.2B, common equity of $3mm, net income of $84mm, and negative comprehensive income of $414mm. Tyson Foods, or $TSN, is in roughly the same valuation range with a tiny common equity of $45mm, a market capitalization of $19.2B, and comprehensive earnings of $1.5B, although earnings fell the most recent quarter and may not be reflected in our annualized data. Assuming our premium market data services balance sheet and income statement data is correct, and we have not checked it, we see a real question. Why do companies run so lean? Why do companies maintain an 'asset light' positioning where they match assets to liabilities? Why doesn't the market punish those companies with lower equity valuations? On the flip side, there are companies with significant amounts of assets, well in excess of liabilities, but they are valued very little above their assets? In fact, many companies are valued below their net assets, or book value, and in theory are worth more dead (or taken through BK) than alive. We don't know the answer to this weighty question, but it is worth further reflection. In addition, we are not sure we would remove companies from evaluation just because they are asset light, or even hold negative net assets. It is just a different way to invest. We see another question. Why do companies trade below their book value? Other companies trade at a discount to book value. $C Citigroup Inc. and $X United States Steel Corp. are two examples of companies that trade at around half of book value. However, Citigroup lost $32.2B on a comprehensive basis last year (ouch), while United States Steel made $1.26B on a comprehensive basis. Accounting for leverage from debt, Citigroup carries a debt to equity ratio of 3.0, while USX is 0.77. If you believe in the power of numbers, US Steel looks like a steal. The question is then about whether those assets can be sold or monetized for their book value. A steel mill, especially during a recession, is probably not easy to sell. Companies are reducing production and shuttering mills. For Citigroup, the answer is likely much more complex as those assets may contain illiquid investments like derivatives, options, stocks, foreclosed collateral, and private equity stakes. During an economic downturn, those assets may be close to worthless (as they were in the Great Financial Crisis of 2007 - 2010). After thinking this through, I am not sure we would include or eliminate a company based on its common equity. It is too complicated to just say, book value = market value. So, we leave our analysis as-is as it relates to book value ratios. In the chart above, we compare US Steel Corporation (red) against two major competitors, $NUE Nucor (purple line, 2.24x market cap / common equity) and $CLF Cleveland Cliffs (blue line, 1.06x). Being 'cheap' relative to book value might be an inverse indicator. Nucor has the highest valuation relative to their net asset position (or common equity), and that valuation continues to grow more quickly. Cleveland Cliffs is in the middle for both valuation and increase. In short, Nucor isn't 'cheap' but it has been the best investment over the past 5 years.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Stock Market BLOGJeffrey CohenPresident and Investment Advisor Representative Archives

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed